- Definition and Importance:

- Laser pointer retinal injuries result from exposure to high-powered handheld laser devices, causing photic maculopathy with damage to the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and outer retinal layers.

- Increasingly common due to the availability of powerful (>5 mW), often mislabeled laser pointers purchased online.

- Particularly concerning in children, who lack protective blink reflexes and have clearer ocular media, increasing susceptibility to retinal damage.

- Study Overview:

- Published in Eye (2019) by Linton et al., combining:

- Literature review: 84 cases of laser pointer retinal burns in children (≤18 years) identified up to March 2018.

- Survey: Online survey of 990 UK consultant ophthalmologists (15.5% response rate) identifying 159 cases of macular injury.

- Case series: Four children (seven eyes) with self-inflicted retinal burns, followed for over 12 months.

- Policy discussion: Engagement with UK stakeholders and review of legislative changes.

- Published in Eye (2019) by Linton et al., combining:

- Demographics and Epidemiology:

- Survey Findings:

- 159 cases of macular injury reported; 80% in patients <20 years, 85% male.

- 54% of injuries occurred within the year prior to the survey (2016).

- Literature Review:

- 84 cases in children ≤18 years; four cases explicitly noted psychological or behavioral issues (e.g., ADHD, learning difficulties, psychiatric evaluation).

- Case Series:

- Four children (three with behavioral/mental health issues: Pathological Demand Avoidance [PDA], ADHD, complex behavioral challenges).

- All injuries were self-inflicted, with persistent outer retinal damage on spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT).

- Survey Findings:

- Key Risk Factors:

- Behavioral and Psychological Conditions:

- Children with ADHD, PDA, autism, or other behavioral issues are at higher risk due to impulsive or obsessive behaviors and reduced adherence to safety instructions.

- Self-injurious behavior (SIB) prevalence in autism: 35–60%; laser pointer misuse identified as a novel form of ocular SIB.

- High-Powered Lasers:

- Devices >50 mW (Class 3B or 4) in 33% of survey cases; often mislabeled as safer Class 2 (<1 mW).

- Misclassification increases risk, as parents and children may underestimate danger.

- Online Availability:

- Most laser pointers purchased online, often lacking proper labeling or warnings.

- Young Age:

- Children have clearer ocular media and reduced protective reflexes (e.g., blink, gaze aversion), increasing retinal exposure.

- Prolonged Exposure:

- Self-inflicted injuries often involve prolonged or repeated exposure, worsening damage.

- Behavioral and Psychological Conditions:

- Clinical Features:

- Presentation:

- Often asymptomatic or with vague visual complaints (e.g., central scotoma, blurred vision).

- Diagnosis delayed in some cases due to hesitation to admit laser use or misdiagnosis as macular dystrophies/inflammation.

- Visual Acuity Outcomes:

- Survey: 36% had moderate vision loss (6/18–6/60 Snellen), 17% severe (<6/60), 15% unaffected.

- Literature Review: At presentation, 36% had 6/18–6/60, 28% <6/60; final acuity 24% at 6/18–6/60, 5% <6/60.

- Case Series: Persistent structural damage in all seven eyes after >12 months, with some improvement in visual acuity.

- SD-OCT Findings:

- Hallmark: Focal disruption of the ellipsoid zone and outer retinal layers.

- Other findings: RPE disruption, outer retinal hyper-reflectivity, occasionally macular holes or hemorrhages.

- Persistent outer lamellar layer defects in case series after >12 months.

- Differential Diagnosis:

- May mimic macular dystrophies, solar retinopathy, or inflammatory maculopathies.

- Key differentiator: History of laser exposure and SD-OCT showing photic maculopathy changes (vs. progressive genetic conditions).

- Presentation:

- Diagnosis:

- History: Critical to inquire about laser pointer exposure, especially in children with unexplained macular changes or behavioral issues.

- Imaging:

- SD-OCT: Gold standard; shows focal ellipsoid zone disruption diagnostic of photic maculopathy.

- Fundus Autofluorescence: May show hypo- or hyper-autofluorescence at injury sites.

- Visual Fields: Central or paracentral scotomas.

- Challenges:

- Delayed diagnosis due to misdiagnosis (e.g., macular dystrophies, as seen in two case series patients and 5/16 in a Moorfields study).

- Reluctance of children/parents to disclose laser use.

- Management:

- No Definitive Treatment:

- Management is largely observational; anecdotal use of oral corticosteroids reported but lacks evidence.

- Monitor with SD-OCT and visual acuity testing.

- Prevention:

- Educate parents, teachers, and carers about ocular risks, especially for children with behavioral issues.

- Restrict access to high-powered lasers (>1 mW) for children.

- Counseling:

- Address psychological/behavioral issues; refer to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) if needed (e.g., two of four case series patients).

- No Definitive Treatment:

- Regulatory and Policy Insights:

- Laser Classifications:

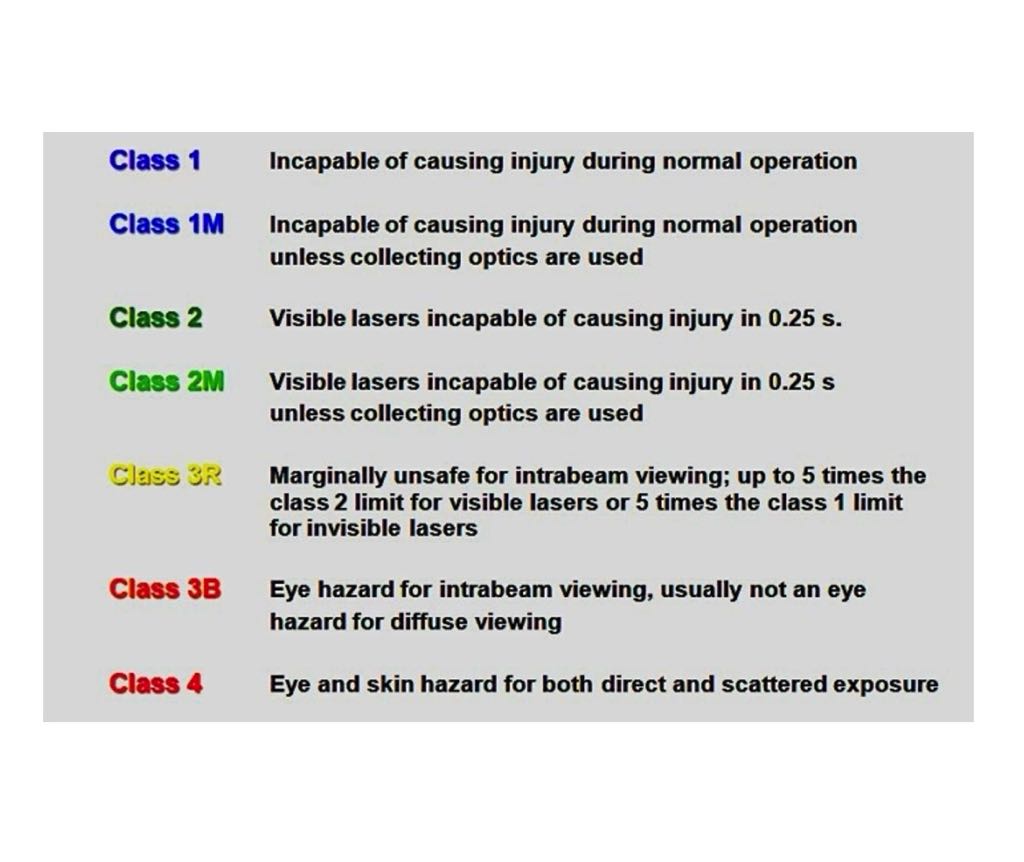

- UK: Class 1, 1C, 1M, 2, 2M, 3R, 3B, 4; Class 2 (<1 mW) recommended for public use.

- US: FDA permits up to Class IIIa (<5 mW); higher classes pose significant risk.

- Misclassification common (e.g., Class 3B labeled as Class 2), increasing ocular hazard.

- UK Policy Changes:

- 2016: Public Health England (PHE) launched an awareness video on laser hazards.

- 2017: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy called for evidence on laser pointer risks.

- 2018: Laser Misuse (Vehicles) Act criminalizes targeting vehicles with lasers (up to 5 years imprisonment).

- 2018: Government response to evidence call: Enhanced import enforcement, better labeling, and public awareness campaigns.

- 2016: Conviction of a seller for a laser causing eye injury in a child, highlighting enforcement efforts.

- Ongoing Concerns:

- Online sales of high-powered, mislabeled lasers remain a challenge.

- Labels (e.g., “Class 3R”) are not consumer-friendly and may falsely reassure parents.

- Laser Classifications:

- Strengths of Study:

- Mixed-methods approach (literature review, survey, case series, policy engagement).

- Highlights novel risk in children with behavioral issues, previously underreported.

- Long-term follow-up (>12 months) in case series, confirming persistent damage.

- Engagement with UK stakeholders (PHE, Royal College of Ophthalmologists) to drive policy change.

- Limitations:

- Low survey response rate (15.5%), limiting epidemiological accuracy.

- Small case series (four children), requiring larger studies for generalizability.

- Lack of formal incidence data; suggests need for British Ophthalmic Surveillance Unit (BOSU) studies.

- Limited reporting of behavioral profiles in literature, potentially underestimating risk.

- Key Takeaways for Exams:

- High-Risk Group: Children with behavioral/mental health issues (e.g., ADHD, autism, PDA) are prone to self-inflicted laser injuries due to impulsive/SIB tendencies.

- Diagnosis: SD-OCT is critical; focal ellipsoid zone disruption is diagnostic. Always inquire about laser exposure in children with macular changes.

- Outcomes: Moderate (6/18–6/60) to severe (<6/60) vision loss in 53% of survey cases; persistent structural damage common.

- Prevention: Restrict access to lasers >1 mW, educate parents, and enhance regulatory enforcement.

- Policy: UK advancements (e.g., 2018 Laser Misuse Act, PHE campaigns) aim to curb risks, but online sales remain a concern.

- Differential: Rule out macular dystrophies; laser injuries may improve slightly, unlike genetic conditions.

Citation

Linton E, Walkden A, Steeples LR, et al. Retinal burns from laser pointers: a risk in children with behavioural problems. Eye. 2019;33:492–504. doi:10.1038/s41433-018-0276-z