Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Management, and Study of Autoimmune Retinopathy (AIR)

– AIR definition: Rare retinal degeneration mediated by anti-retinal antibodies, categorized as non-paraneoplastic (npAIR), cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR), or melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR).

– Task Force goal: Provide a standardized diagnostic framework, management guidelines, and research recommendations for AIR, focusing on npAIR due to its diagnostic complexity.

– Literature review: Conducted via PubMed and Google Scholar (no date restrictions, up to September 2024) to inform expert consensus.

– Epidemiology and Clinical Features:

– Demographics: Predominantly middle-aged/older women (~66%), often with personal/family history of autoimmune disease. npAIR affects younger patients than CAR.

– Symptoms: Painless photopsias, nyctalopia, photoaversion, dyschromatopsia, peripheral/paracentral scotomas, progressing over weeks to months (vs. years in IRDs).

– Presentation: Bilateral but may be asymmetric early; central vision preserved initially, with rapid progression distinguishing AIR from indolent IRDs.

– Exam findings: Early—minimal retinal changes; late—pigmentary changes, vessel attenuation, disc pallor (mimics IRDs); bone spicules rare in AIR.

– Diagnostic Framework:

– Proposed classification: Categorizes patients as probable, possible, or unlikely AIR to standardize diagnosis and research (Table 1).

– Probable AIR (requires all):

– Disease progression (symptoms/objective tests) within 6 months.

– <1+ anterior chamber/vitreous cell/haze.

– OCT: Outer retinal disruption (loss of external limiting membrane/ellipsoid zone), often sparing fovea.

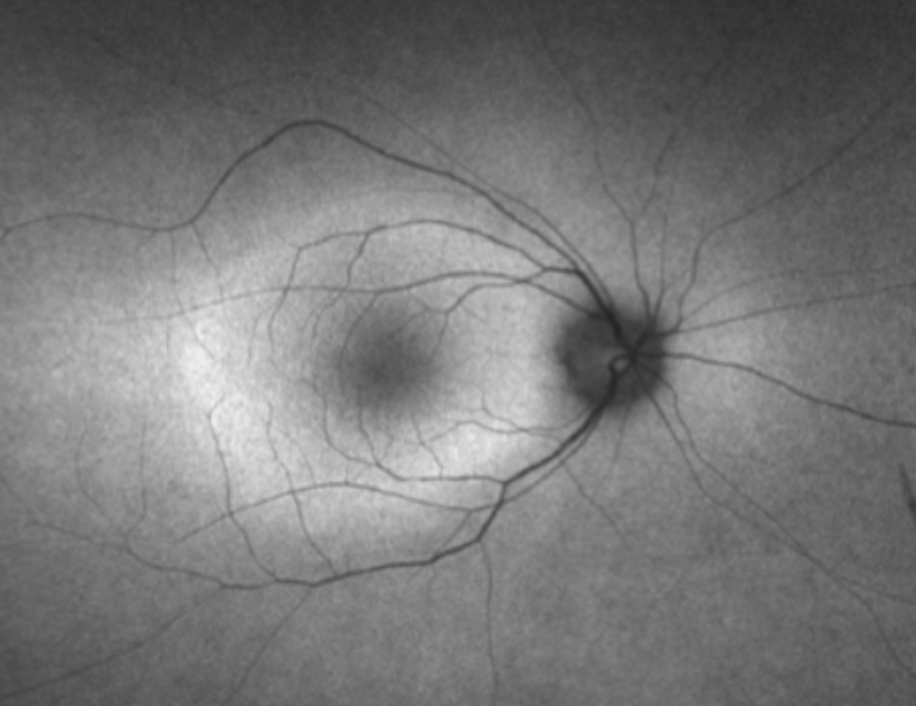

– FAF: Abnormal patterns (e.g., parafoveal hyperautofluorescent ring, perimacular/peripapillary hypoautofluorescence).

– Full-field ERG: Reduced rod and cone responses.

– Positive anti-retinal antibodies.

– Possible AIR: Some but not all probable features, without unlikely features; requires close monitoring for progression.

– Unlikely AIR (any of):

– Slow progression (>years).

– Bone spicules, vascular sheathing, retinal hemorrhages.

– >1+ intraocular inflammation.

– OCT: RPE-predominant changes or sharply delineated atrophy.

– FA: Diffuse vasculitis or large non-perfusion areas.

– Normal full-field ERG (even if multifocal ERG abnormal).

– Negative anti-retinal antibodies (repeat testing after 6 months if other features present).

– Imaging and Testing:

– OCT: Ellipsoid zone loss with parafoveal tapering (92% of cases per Xu et al.), foveal sparing late; cystoid macular edema in 24%; RPE changes atypical.

– FAF: Hyperautofluorescent ring (33% at baseline, 75% at follow-up), perimacular/peripapillary hypoautofluorescence (83%, asymmetric); contrasts with symmetric IRD patterns.

– FA: Mild vascular leakage/staining possible; diffuse vasculitis/non-perfusion suggests uveitis, not AIR.

– ERG: Non-specific reductions in rod/cone responses; electronegative ERG classic for MAR (TRPM1 antibodies); normal full-field ERG rules out AIR.

– Visual fields: Peripheral constriction, central/paracentral scotomas; rapid loss (months) vs. slow IRD progression (years).

– Anti-retinal antibodies:

– Low specificity: Positive in non-AIR conditions, healthy controls; adjunct test, not confirmatory.

– Testing methods: Western blot, line blot, ELISA, immunohistochemistry (IHC); Western blot + IHC most common but non-standardized (57–60% lab concordance).

– Interpretation: Multiple antibodies may increase AIR likelihood; recoverin specific for CAR; negative test doesn’t rule out AIR (rare).

– Genetic testing:

– Recommended for atypical cases due to IRD overlap (e.g., HGSNAT, DRAM2, RP1 variants).

– Limitations: ~60% sensitivity; negative test doesn’t exclude IRD; variants of unknown significance (VUS) require expert interpretation.

– Differential Diagnosis:

– Key mimics: Late-onset IRDs, drug toxicity (e.g., hydroxychloroquine, pentosan), vitamin A deficiency, inflammatory conditions (e.g., syphilis, birdshot chorioretinopathy, white-dot syndromes).

– Distinguishing features:

– IRDs: Childhood symptoms, slow progression, family history, bone spicules.

– Uveitis: >1+ inflammation, vasculitis, retinitis/choroiditis on imaging.

– Toxicity: Pericentral retinopathy (hydroxychloroquine, especially in Asians).

– Systemic Evaluation:

– Cancer screening: Essential to differentiate npAIR from CAR/MAR; includes body imaging, dermatologic exam, age-appropriate tests (e.g., mammography, colonoscopy).

– CAR: Commonly small-cell lung cancer; cancer may present years after AIR.

– MAR: Usually pre-existing metastatic melanoma.

– Repeat screening: Limited value unless new symptoms; maintain routine cancer screenings.

– Management:

– No standardized guidelines due to limited data (case reports/series).

– Goal: Prevent progression (visual improvement rare).

– Therapies:

– Corticosteroids (local/systemic): May improve macular edema, ellipsoid zone integrity.

– Immunomodulators: Antimetabolites, T-cell inhibitors, rituximab (targets B-cells, reduces antibodies), IVIG.

– Others: Plasmapheresis (no consensus), bortezomib (with rituximab, possible ERG benefit).

– Challenges:

– Delayed effect: Stabilization may take ≥1 year.

– Heterogeneity: Variable natural history complicates treatment decisions.

– End-stage disease: May not progress, questioning therapy need.

– Monitoring: Every 3–6 months with exam, OCT, FAF, visual fields, ERG; antibody titers not routinely retested (poor reproducibility).

– Research Recommendations (Table 2):

– Standardization: Use probable/possible/unlikely AIR classification in studies.

– Epidemiology: Establish incidence/prevalence, create ICD codes for AIR/CAR.

– Natural history: Develop multi-center registries to study triggers, mechanisms, and progression.

– Antibodies: Standardize assays (Western blot, line blot, IHC), define sensitivity/specificity, assess titer changes for treatment response.

– Treatment: Conduct RCTs (e.g., rituximab), define success metrics, identify prognostic biomarkers.

– Education: Increase awareness, improve diagnostic accuracy.

– Strengths:

– First standardized framework for AIR diagnosis, addressing historical inconsistency.

– Comprehensive: Integrates clinical, imaging, ERG, antibody, genetic data.

– Research focus: Proposes actionable steps for registries, trials, and collaboration.

– Limitations:

– Non-specific features: All criteria individually overlap with IRDs, uveitis, etc.

– Antibody testing: Low specificity, variable results across labs.

– Evidence gap: No RCTs, limited treatment data, unclear natural history.

– Early diagnosis: Subtle findings delay confirmation, risking irreversible damage.

These points emphasize the new diagnostic classification, overlap with IRDs/uveitis, role of anti-retinal antibodies, and need for multicenter research.